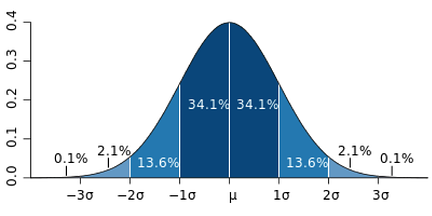

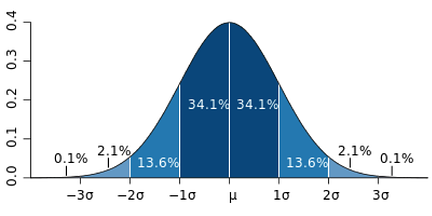

As a society, we have been conditioned to reward based on a bell curve. Starting in secondary education and continuing into adulthood, it has been a long-standing belief that human performance follows a normal distribution: few high performers, few low performers, and the majority sitting on the average.

As a society, we have been conditioned to reward based on a bell curve. Starting in secondary education and continuing into adulthood, it has been a long-standing belief that human performance follows a normal distribution: few high performers, few low performers, and the majority sitting on the average.

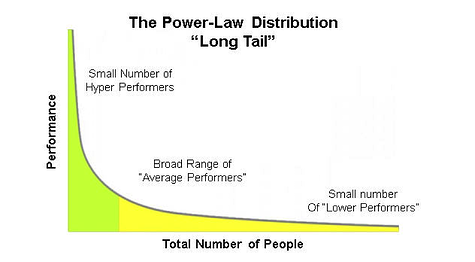

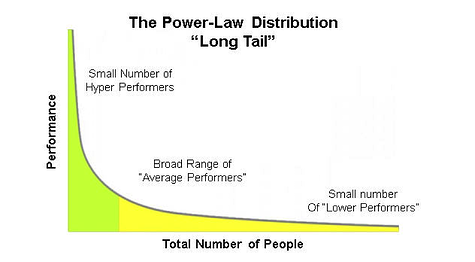

Recent research, however, shows that business practices based on the bell curve are counterproductive. In actuality, unless your hiring practice involves using random selection, their performance will not fall perfectly on a normal distribution. Rather, it will follow a long tail distribution.

Recent research, however, shows that business practices based on the bell curve are counterproductive. In actuality, unless your hiring practice involves using random selection, their performance will not fall perfectly on a normal distribution. Rather, it will follow a long tail distribution.

Josh Bersin, in The Myth of the Bell Curve, argues that performance falls into the Power Law distribution. This suggests that there will always be a small number of ‘hyper high performers’, and a large majority of ‘good performers,’ and a small number of ‘low performers.’ In other words, most people will fall below the mean and only a small number of ‘hyper high performers’ will be above mean. This suggests that the concept of an average is fundamentally irrelevant in the context of employee performance.

Josh Bersin, in The Myth of the Bell Curve, argues that performance falls into the Power Law distribution. This suggests that there will always be a small number of ‘hyper high performers’, and a large majority of ‘good performers,’ and a small number of ‘low performers.’ In other words, most people will fall below the mean and only a small number of ‘hyper high performers’ will be above mean. This suggests that the concept of an average is fundamentally irrelevant in the context of employee performance.

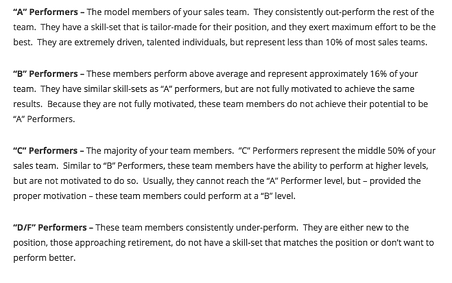

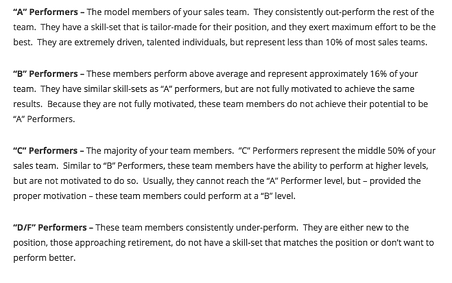

Nevertheless, there are many organizations that structures their incentive programs based on the normal distribution. For instance, employers may choose to ‘grade’ their employees by five performance levels: A, B, C, D, and F.

Unknowing to them, this system is damaging to employees.

Unknowing to them, this system is damaging to employees.

In truth, the majority of your team actually consists of ‘good performers,’ and when you are forcing them into the bell curve, you are inaccurately relabeling them as ‘below average performers.’ The bell curve will also require you to create a class of ‘losers’ that are in the bottom 10%, who may actually not be deserving of that label at all.

Despite good intentions, ranking based on a normal distribution is counterproductive. If you didn’t agree with the bell curve system in school, what makes you think your employees would like it?

The fact is, grading employees’ year worth of work on a five point scale is demeaning. Moreover, it causes your ‘B and C performers’ to feel under-appreciated. Bersin also claims that this model rewards mediocrity because your mid level performers will give up trying, if only a small select number of people will be ‘A performers.’

So what is the right way to motivate your employees?

Classic managerial literature says invest in top performers and cut out the lowest performers. That leaves us to thinking, what about the middle 80 percent? How do you push your good performers to become hyper performers? George Bradt argues in How to Motivate the Middle 80 Percent, that the best way to motivate the majority is to create short bursts of contests where everyone has the equal opportunity and ability to win.

When you are creating a contest that rewards only the same hyper performers, you are not motivating anyone. Your hyper performers would have won without the contest. Winning contests is great but their commissions and bonuses have already motivated them. On the other hand, the contest may have motivated your good performers at one point but it failed to have a persisting impact when they concluded that they did not have the chance to win.

To avoid wasting resources and furthering employee discouragement, design a contest that gives everyone the optimism that they can win. Don’t just focus on results. Measure a variety of metrics and provide your employees multiple ways to win. Include ‘activity metrics’ such as number of completed visits, number of missed visits, or number of clients visited. To avoid losing your employee’s attention, reset the contest every 30 to 60 days and update results frequently. Lastly, while an all expenses paid vacation to Hawaii would be a great prize, you should not be spending big portions of your budget on these contests. Small, meaningful prizes like gift cards, movie tickets, or allowing them to bring their pets to work can make your employees feel appreciated.

As a society, we have been conditioned to reward based on a bell curve. Starting in secondary education and continuing into adulthood, it has been a long-standing belief that human performance follows a normal distribution: few high performers, few low performers, and the majority sitting on the average.

As a society, we have been conditioned to reward based on a bell curve. Starting in secondary education and continuing into adulthood, it has been a long-standing belief that human performance follows a normal distribution: few high performers, few low performers, and the majority sitting on the average. Recent research, however, shows that business practices based on the bell curve are counterproductive. In actuality, unless your hiring practice involves using random selection, their performance will not fall perfectly on a normal distribution. Rather, it will follow a long tail distribution.

Recent research, however, shows that business practices based on the bell curve are counterproductive. In actuality, unless your hiring practice involves using random selection, their performance will not fall perfectly on a normal distribution. Rather, it will follow a long tail distribution. Josh Bersin, in

Josh Bersin, in  Unknowing to them, this system is damaging to employees.

Unknowing to them, this system is damaging to employees.